As Flash, Montgomery County’s Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system, slowly comes together, could it (eventually) transform how people get around?

FLASH BRT in Silver Spring, Maryland by MW Transit Photos licensed under Creative Commons.

This is Part II of a three-part series on Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) in Montgomery County. Read Part I.

In an ideal world, Montgomery County’s Flash Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system would be built in a flash, an interconnected network whisking people to all corners of the county, as has long been planned. Yet financial issues mean that the network is being built slowly, piece by piece, while local conditions and plans mean that large segments end up running in mixed traffic rather than having lanes of their own.

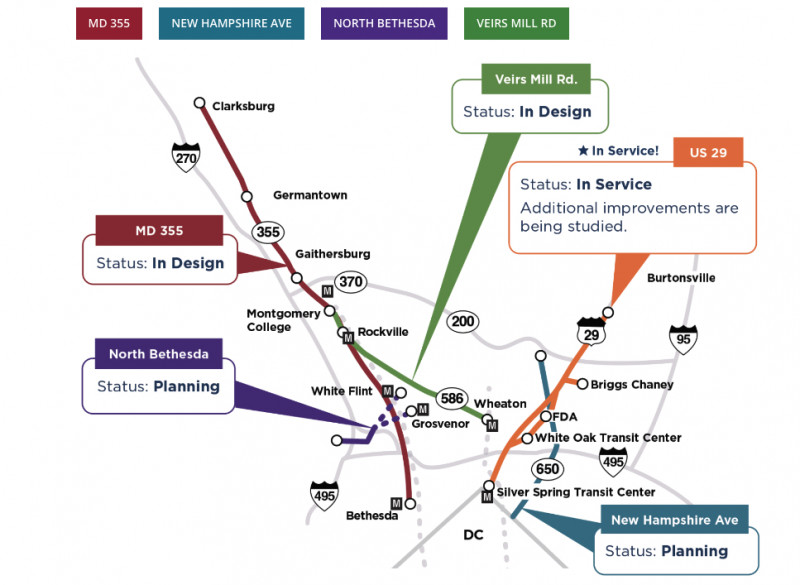

Indeed, transit advocates argue that the first part of the Flash, on US 29, has not done enough to provide dedicated lanes for buses, meaning that they get caught in traffic, and that this sets the wrong tone for the rest of the network. Still, by 2028 the skeleton of the Flash BRT network should be complete, with the US 29 Flash in the east, the Route 355 line in the west, and the Veirs Mill line bridging them, to an extent.

For Montgomery County Executive Marc Elrich, the process has been too slow. “I’m trying to accelerate the timelines,” which “are ridiculous, and they’re all borne of lack of resources, because you don’t have the money,” he told me in a recent interview.

In 2007 when Elrich, then a county council member, first proposed a BRT system, the impetus came from a “horrifically high” projection of a polluted future by the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments, he said. Elrich wanted cleaner air and fewer greenhouse emissions and envisioned a network of buses with their own lanes that could bypass traffic and draw drivers out of their cars. Removing about 8% of cars would result in free-flowing traffic, according to Dale Tibbets, Special Assistant to Marc Elrich, and everyone would benefit.

At the time, Elrich said, he believed that Montgomery County could get a jump on other jurisdictions in designing and building a complete network, and hence an economic boost. In 2014, northern Virginia beat Montgomery County to the first BRT line—the Metroway, which has dedicated lanes in the median. And now, 15 years after the Montgomery County network was first proposed, northern Virginia is advancing plans for a region-wide network.

Elrich argued that an inadequate financing mechanism has been the major factor slowing down BRT in Montgomery County. He pointed to Virginia’s special tax districts as able to raise dedicated funds for transit, providing “a stream of money that you can bond against.” Such a scheme is also amenable to businesses, Elrich argued, since they know that they are getting something tangible, namely transit to directly support their business. “If I have to compete with Virginia, I want the same tools,” said Elrich. “If somebody’s eating your lunch you should figure out how they got it, and … it’s just really clear that [Virginia’s] decisions were better than our decisions.”

Whatever the obstacles, MCDOT’s long-term vision is to build a transformative network. In the long run, the network is planned to be fully connected, north to south and east to west. Furthermore, “our goal was to get as much transit priority as possible in dedicated lanes,” said Joana Conklin, Bus Rapid Transit Program Manager, Montgomery County Department of General Services. When the network is built out, “I really do believe that the BRT projects do have the potential to be transformational,” she added. “We don’t really have a choice … . If you look at population and employment projects for the county, we’re going to keep growing, and there really isn’t the desire, or even feasibility, to expand the roadways.”

Map of current and planned BRT routes throughout Montgomery County. Image by Montgomery County Department of Transporttion.

A skeletal network is beginning to form

Meanwhile, passengers can await the three Flash lines projected to be built first, with the last coming into service around 2028. Route 355 will have dedicated lanes in the median along most of its length, “about 65 or 70%,” said Corey Pitts, Planning Section Chief, Montgomery County Department of Transportation (MCDOT). Gaithersburg will not have dedicated lanes “based on their current input,” he added. At times, Route 355 Flash will have a single reversible lane to change with the flow of traffic, while as much as possible there will be two dedicated lanes. Initially, this route will come the closest to fulfilling Flash’s original vision.

The Veirs Mill line will improve on current dedicated lanes along the side, which currently are easily encroached on by cars. “It’s not well marked, so you do see a lot of people violating it,” said Conklin. “More visual cues for the driver” will have “a pretty big impact.”

Pitts mentioned red pavement and enforcement as ways to improve exclusivity of dedicated bus lanes. Still, the bulk of the Veirs Mill line will operate in mixed traffic, although it will use queue jumps and transit signal priority to speed up. However, the Veirs Mill line is likely to be upgraded, with additional dedicated lanes, in coming years. Two other routes, New Hampshire and North Bethesda, are still in the planning phase and awaiting funding.

There is an obvious hole in the configuration of the initial three lines, between Wheaton, where the Veirs Mill line currently ends, and Silver Spring where the Route 29 line begins. Flash service between Wheaton and Silver Spring would be one way to connect the routes, while another alternative would be to extend the Veirs Mill line east to hook up with Route 29. Conklin explained that it’s difficult to build the entire project at once, but complementary projects with quicker builds, basically express buses similar to the existing Ride On Extra, can fill in the gap for the time being. In the longer run, BRT routes on University and Randolph Road will add east-west connectivity.

Rather than considering Flash as its own independent network, it is more realistic to look at it as part of a larger transit network, including Metrorail, Metro and Ride On buses, and the Purple Line. Indeed, once the first three BRT lines are running, the Purple Line will form a major east-west link that is otherwise missing. In reality, people will plan their trips using whatever transit mode is most convenient, often hopping from a BRT line onto the Purple Line and vice versa.

Conklin compared it to the road system with different classifications— highways, arterials, and local neighborhood streets. Similarly, transit has commuter rail, Metrorail and Metrobus, Ride On bus, the forthcoming Purple Line, and BRT.

The most local part of the network, the capillaries feeding major arteries, is Ride On. Yet the county has already begun experimenting with a service that users can call to specific neighborhoods, Flex Bus. Eventually, this is likely to complement Ride On and perhaps even supplant it. For neighborhoods otherwise difficult to serve, Flex, “can really get in and get closer to where people live,” said Conklin. “All of these things have to work together to make it as seamless as possible for people to get around without a car.”

It may be a long time coming, but at some point, Montgomery County will likely have a transformative network that makes car ownership less of an imperative and greatly aids the fight against climate change while providing transportation equity.